No Bad Boys: ‘Heart of a Servant, the Father Flanagan Story’

Written by Brad Miner

Tuesday, September 24, 2024

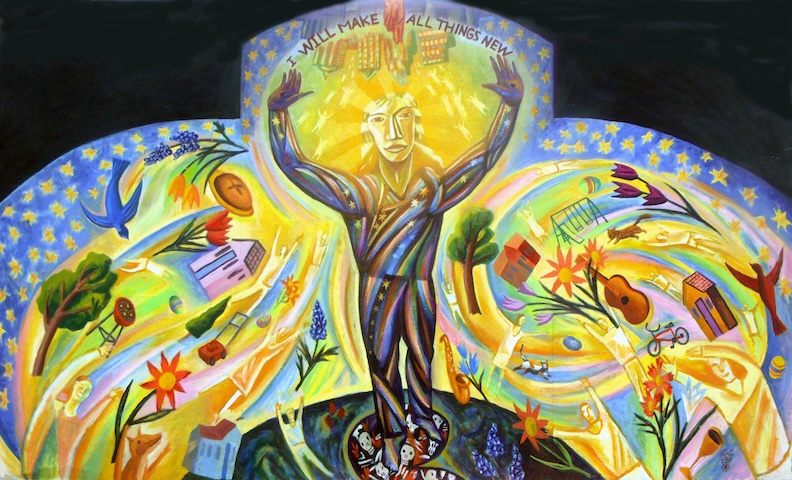

It was originally called “The City of Little Men,” when the Irish-born Fr. Edward J. Flanagan founded the refuge for orphaned and troubled boys in 1917 at 25th and Dodge Streets in Omaha. It became Boys Town a few years later when Fr. Flanagan purchased a farm – a necessary investment since the number of boys under his care had grown from a few to a few hundred. By the 1960s, the population of Boys Town peaked at 880.

A new documentary film – premiering October 8th in one-night-only, nationwide Fathom Events screenings – seems intended to boost the cause of Servant of God Fr. Flanagan’s canonization. Surely, it will help, as people see the documentary, are inspired by the great man’s story, and begin to pray for his intercession.

Edward Joseph Flanagan was born in 1886 in Leabeg, County Roscommon, emigrated to the United States in 1904, and was educated at Mount St. Mary’s College in Maryland, after which he went to Dunwoodie, as we New Yorkers call it: St. Joseph’s Seminary in (the Dunwoodie section of) Yonkers, NY, which in those days was known as the West Point of American seminaries.

He spent time at the Gregorian University in Rome in 1908 but was forced to take a break because of ill health. (He had been dealing with respiratory and cardiac issues since birth.) His journey continued in, of all places, the Royal Imperial Leopold Francis University in Innsbruck, Austria – in part because it was assumed the mountain air would be good for his lungs – and was ordained there in 1912.

He returned to America and joined his older brother, Patrick, also a priest, and his sister, Nellie, in Omaha.

For the rest of the column, click here . . .